研究人员揭开植物进化对抗寒冷之谜

来源:《Nature》

作者:Amy E. Zanne

时间:2014-01-06

由乔治华盛顿大学、田纳西大学等机构的研究人员组成的一支国际科研小组日前在《自然》(Nature)杂志上报告称,他们发现了植物如何进化为对抗寒冷天气的新线索。

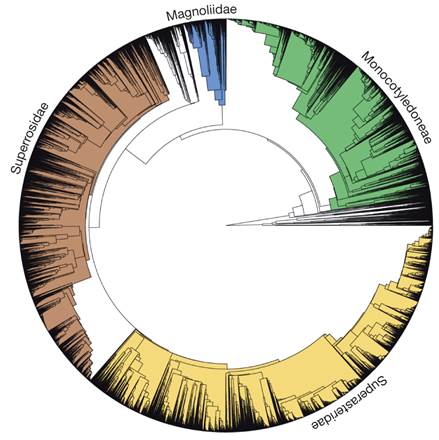

在这项研究中,论文主要作者、田纳西大学国家数学和生物合成研究所(NIMBioS)教授 Jeremy Beaulieu 和他的同事们构建了超过 3.2 万种开花植物的进化树——迄今最大时间刻度的进化树。通过将此进化树,与冷冻暴露记录和数千种植物的叶片/茎干数据进行比较,研究人员能够重现,当植物在全球范围内传播时,它们是如何进化为对抗寒冷的。

结果表明,许多植物,在它们第一次遭遇冰冻以前很久,就获得了有助于其在更冷气候中茁壮成长的特性(例如在冬天彻底死掉)。Beaulieu 表示,化石证据和过去气候条件的重现都表明,早期的开花植物生活在温暖的热带环境。

当植物扩散到高纬度和高海拔地区时,它们以有助于其对抗寒冷条件的方式进化。生活在北极苔原的植物,例如北极委陵菜和三齿虎耳草,能够抵御冬季低于零下 15 摄氏度的气温。

与动物不同,植物不能通过移动来逃避寒冷,也不能产生热量来保暖。与其说是寒冷,不如说是冰冻给植物带来了问题。例如,冻融引起植物体内水运输系统中气泡的形成。

论文的共同作者、乔治华盛顿大学的 Amy Zanne 表示:“想一想你在冰块中看到的悬浮的气泡。如果足够多的这种气泡集合在一起,当水解冻时,它们就能阻止水从根部流向叶片,从而杀死植物。”

研究中,科学家确定了三种特征,能够帮助植物应付这些问题。有些植物,例如胡桃和橡树,在冬天寒冷来临前通过落叶来避免冻害——有效地切断根部和叶片之间的水流,当天气转暖时,长出新的叶片和水运输细胞。其他的植物,例如桦树和白杨,也通过具有较狭窄的水运输细胞来保护自己,这使得运输水分的植物部分,在冻结和解冻过程中不易堵塞。还有一些植物在冬天彻底死掉,当环境转暖时再从根部重新发芽,或者从种子长成新的植物。

为了收集这项研究的植物特征数据,研究人员花了数百个小时搜索和合并包含成千上万种植物的多个大数据库。当研究人员将其收集的叶片和茎部数据,映射到他们所构建的开花植物进化树上时,他们发现,许多植物,甚至在寒冷条件袭击之前,就已经全副武装来应对寒冷气候。例如,在冬季会彻底死掉的植物,在它们第一次经历冰冻以前很久,就获得了枯死、然后在环境转暖又恢复原状的能力。同样地,具有狭窄水运输细胞的物种,在它们面对寒冷气候之前,就获得了更好的循环系统。

Zanne 表示:“这表明,其它一些环境压力——可能是干旱——使这些植物以这种方式进化,这正好这也有利于植物的抗冻性。”Beaulieu 则补充说道:”唯一的例外是那些季节性落叶和换叶的植物,这些植物类群只有在其遭遇冰冻之后才获得在冬季落叶的能力。“他们计划下一步使用他们的进化树,发现植物如何进化到抵抗除冰冻之外的其它环境压力,例如干旱和高温。(转自:生物谷360 http://www.bio360.net/news/show/8493.html)

Three keys to the radiation of angiosperms into freezing environments

Abstract Early flowering plants are thought to have been woody species restricted to warm habitats1, 2, 3. This lineage has since radiated into almost every climate, with manifold growth forms4. As angiosperms spread and climate changed, they evolved mechanisms to cope with episodic freezing. To explore the evolution of traits underpinning the ability to persist in freezing conditions, we assembled a large species-level database of growth habit (woody or herbaceous; 49,064 species), as well as leaf phenology (evergreen or deciduous), diameter of hydraulic conduits (that is, xylem vessels and tracheids) and climate occupancies (exposure to freezing). To model the evolution of species’ traits and climate occupancies, we combined these data with an unparalleled dated molecular phylogeny (32,223 species) for land plants. Here we show that woody clades successfully moved into freezing-prone environments by either possessing transport networks of small safe conduits5 and/or shutting down hydraulic function by dropping leaves during freezing. Herbaceous species largely avoided freezing periods by senescing cheaply constructed aboveground tissue. Growth habit has long been considered labile6, but we find that growth habit was less labile than climate occupancy. Additionally, freezing environments were largely filled by lineages that had already become herbs or, when remaining woody, already had small conduits (that is, the trait evolved before the climate occupancy). By contrast, most deciduous woody lineages had an evolutionary shift to seasonally shedding their leaves only after exposure to freezing (that is, the climate occupancy evolved before the trait). For angiosperms to inhabit novel cold environments they had to gain new structural and functional trait solutions; our results suggest that many of these solutions were probably acquired before their foray into the cold.

原文链接:http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/vaop/ncurrent/full/nature12872.html#/references